A collage of personal, political,cultural, and historical commentary from the thought processes of Brandon Wallace.

Saturday, December 31, 2011

Adieu, 2011

2011 was not a bad year for me....some things did happen though that did define the year and may prove monumental....I lost my grandmother in February, Hello Thelma, wherever you may be in the universe....I did feel it a great privilege and honor that the universe chose me to take care of you in your final chapter....I finally put into play my first publication as a writer. My poetry collection, Shadow and Act is due to be published in January by Llumina Press. I am glad that I pushed forward to bring my destiny into reality....and I have hope for my future....I learned a lot of things about myself this year...as I am continually doing throughout this life...and finally I am beginning to feel a bit of pep in my step to go out and do what needs to be done....This new season will see PHD applications and hopefully lots of movement, TONS of movement....I am going to throw myself onto the universe and consciously ride it to where ever destiny takes me....One thing that I have decided is that I will celebrate more...and celebrate myself.... to use the words of Nikki Giovanni "this is about us....celebrating ourselves...and a well deserved honor it is...Light the candles Essence...this is a rocket...let's ride...."

Tuesday, December 27, 2011

President Obama: Veto Indefinite Detention

From the ACLU

As I write this, the Defense Authorization bill is on its way to President Obama's desk. The bill contains dangerous, sweeping worldwide indefinite detention provisions.

Leading members of Congress have already indicated that they believe that these provisions could be used by this and any future president to indefinitely detain people without charge or trial — even American citizens and others picked up within the borders of the United States.

According to reports, the President's advisors are recommending that he not veto this legislation despite earlier promises to do so. We need to tell the President to listen to the American people.

There are moments in America when our freedoms depend on the willingness of a President to act firmly and decisively to sustain our fundamental values; moments that decide the course our nation takes for years to come.

This is one of those moments. Tell President Obama you’re counting on him to veto indefinite detention and uphold the freedoms and values America was built on.

As I write this, the Defense Authorization bill is on its way to President Obama's desk. The bill contains dangerous, sweeping worldwide indefinite detention provisions.

Leading members of Congress have already indicated that they believe that these provisions could be used by this and any future president to indefinitely detain people without charge or trial — even American citizens and others picked up within the borders of the United States.

According to reports, the President's advisors are recommending that he not veto this legislation despite earlier promises to do so. We need to tell the President to listen to the American people.

There are moments in America when our freedoms depend on the willingness of a President to act firmly and decisively to sustain our fundamental values; moments that decide the course our nation takes for years to come.

This is one of those moments. Tell President Obama you’re counting on him to veto indefinite detention and uphold the freedoms and values America was built on.

Thursday, December 22, 2011

Sunday, December 18, 2011

Saturday, December 17, 2011

Whoopi Goldberg and Jackee in the New Mame!

Ok, this is just a dream in my head--but wouldn't it be a wonderful remake of Mame--with Whoopi Goldberg as Auntie Mame and Jackee as Auntie Vera? Ohhh someone in Hollywood ought to make this film!

Mrs. Elaine Saliba

This post is in homage to my fifth grade math teacher, Mrs. Elaine Saliba, who is in a very large way responsible for me turning out as a writer. Even though she taught me math, she always brought me these writer's books filled with prompts and exercises and other writer's whatnots. I spent my time in her classes writing...and then she'd read my stories and give me feedback....Thanks you, Mrs. Saliba.

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

Saturday, December 10, 2011

A Statement on The Help by The Association of Black Women Historians (ABWH)

Saturday, December 10, 2011

Member Login

ABWH Logo

An Open Statement to the Fans of The Help:

On behalf of the Association of Black Women Historians (ABWH), this statement provides historical context to address widespread stereotyping presented in both the film and novel version of The Help. The book has sold over three million copies, and heavy promotion of the movie will ensure its success at the box office. Despite efforts to market the book and the film as a progressive story of triumph over racial injustice, The Help distorts, ignores, and trivializes the experiences of black domestic workers. We are specifically concerned about the representations of black life and the lack of attention given to sexual harassment and civil rights activism.

During the 1960s, the era covered in The Help, legal segregation and economic inequalities limited black women's employment opportunities. Up to 90 per cent of working black women in the South labored as domestic servants in white homes. The Help’s representation of these women is a disappointing resurrection of Mammy—a mythical stereotype of black women who were compelled, either by slavery or segregation, to serve white families. Portrayed as asexual, loyal, and contented caretakers of whites, the caricature of Mammy allowed mainstream America to ignore the systemic racism that bound black women to back-breaking, low paying jobs where employers routinely exploited them. The popularity of this most recent iteration is troubling because it reveals a contemporary nostalgia for the days when a black woman could only hope to clean the White House rather than reside in it.

Both versions of The Help also misrepresent African American speech and culture. Set in the South, the appropriate regional accent gives way to a child-like, over-exaggerated “black” dialect. In the film, for example, the primary character, Aibileen, reassures a young white child that, “You is smat, you is kind, you is important.” In the book, black women refer to the Lord as the “Law,” an irreverent depiction of black vernacular. For centuries, black women and men have drawn strength from their community institutions. The black family, in particular provided support and the validation of personhood necessary to stand against adversity. We do not recognize the black community described in The Help where most of the black male characters are depicted as drunkards, abusive, or absent. Such distorted images are misleading and do not represent the historical realities of black masculinity and manhood.

Furthermore, African American domestic workers often suffered sexual harassment as well as physical and verbal abuse in the homes of white employers. For example, a recently discovered letter written by Civil Rights activist Rosa Parks indicates that she, like many black domestic workers, lived under the threat and sometimes reality of sexual assault. The film, on the other hand, makes light of black women’s fears and vulnerabilities turning them into moments of comic relief.

Similarly, the film is woefully silent on the rich and vibrant history of black Civil Rights activists in Mississippi. Granted, the assassination of Medgar Evers, the first Mississippi based field secretary of the NAACP, gets some attention. However, Evers’ assassination sends Jackson’s black community frantically scurrying into the streets in utter chaos and disorganized confusion—a far cry from the courage demonstrated by the black men and women who continued his fight. Portraying the most dangerous racists in 1960s Mississippi as a group of attractive, well dressed, society women, while ignoring the reign of terror perpetuated by the Ku Klux Klan and the White Citizens Council, limits racial injustice to individual acts of meanness.

We respect the stellar performances of the African American actresses in this film. Indeed, this statement is in no way a criticism of their talent. It is, however, an attempt to provide context for this popular rendition of black life in the Jim Crow South. In the end, The Help is not a story about the millions of hardworking and dignified black women who labored in white homes to support their families and communities. Rather, it is the coming-of-age story of a white protagonist, who uses myths about the lives of black women to make sense of her own. The Association of Black Women Historians finds it unacceptable for either this book or this film to strip black women’s lives of historical accuracy for the sake of entertainment.

Ida E. Jones is National Director of ABWH and Assistant Curator at Howard University. Daina Ramey Berry, Tiffany M. Gill, and Kali Nicole Gross are Lifetime Members of ABWH and Associate Professors at the University of Texas at Austin. Janice Sumler-Edmond is a Lifetime Member of ABWH and is a Professor at Huston-Tillotson University.

Word Count: 766

Suggested Reading:

Fiction:

Like one of the Family: Conversations from A Domestic’s Life, Alice Childress

The Book of the Night Women by Marlon James

Blanche on the Lam by Barbara Neeley

The Street by Ann Petry

A Million Nightingales by Susan Straight

Non-Fiction:

Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household by Thavolia Glymph

To Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors by Tera Hunter

Labor of Love Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family, from Slavery to the Present by Jacqueline Jones

Living In, Living Out: African American Domestics and the Great Migration by Elizabeth Clark-Lewis

Coming of Age in Mississippi by Anne Moody

Any questions, comments, or interview requests can be sent to: ABWHTheHelp@gmail.com

ABWH Statement The Help (pdf) pdf button

Member Login

ABWH Logo

An Open Statement to the Fans of The Help:

On behalf of the Association of Black Women Historians (ABWH), this statement provides historical context to address widespread stereotyping presented in both the film and novel version of The Help. The book has sold over three million copies, and heavy promotion of the movie will ensure its success at the box office. Despite efforts to market the book and the film as a progressive story of triumph over racial injustice, The Help distorts, ignores, and trivializes the experiences of black domestic workers. We are specifically concerned about the representations of black life and the lack of attention given to sexual harassment and civil rights activism.

During the 1960s, the era covered in The Help, legal segregation and economic inequalities limited black women's employment opportunities. Up to 90 per cent of working black women in the South labored as domestic servants in white homes. The Help’s representation of these women is a disappointing resurrection of Mammy—a mythical stereotype of black women who were compelled, either by slavery or segregation, to serve white families. Portrayed as asexual, loyal, and contented caretakers of whites, the caricature of Mammy allowed mainstream America to ignore the systemic racism that bound black women to back-breaking, low paying jobs where employers routinely exploited them. The popularity of this most recent iteration is troubling because it reveals a contemporary nostalgia for the days when a black woman could only hope to clean the White House rather than reside in it.

Both versions of The Help also misrepresent African American speech and culture. Set in the South, the appropriate regional accent gives way to a child-like, over-exaggerated “black” dialect. In the film, for example, the primary character, Aibileen, reassures a young white child that, “You is smat, you is kind, you is important.” In the book, black women refer to the Lord as the “Law,” an irreverent depiction of black vernacular. For centuries, black women and men have drawn strength from their community institutions. The black family, in particular provided support and the validation of personhood necessary to stand against adversity. We do not recognize the black community described in The Help where most of the black male characters are depicted as drunkards, abusive, or absent. Such distorted images are misleading and do not represent the historical realities of black masculinity and manhood.

Furthermore, African American domestic workers often suffered sexual harassment as well as physical and verbal abuse in the homes of white employers. For example, a recently discovered letter written by Civil Rights activist Rosa Parks indicates that she, like many black domestic workers, lived under the threat and sometimes reality of sexual assault. The film, on the other hand, makes light of black women’s fears and vulnerabilities turning them into moments of comic relief.

Similarly, the film is woefully silent on the rich and vibrant history of black Civil Rights activists in Mississippi. Granted, the assassination of Medgar Evers, the first Mississippi based field secretary of the NAACP, gets some attention. However, Evers’ assassination sends Jackson’s black community frantically scurrying into the streets in utter chaos and disorganized confusion—a far cry from the courage demonstrated by the black men and women who continued his fight. Portraying the most dangerous racists in 1960s Mississippi as a group of attractive, well dressed, society women, while ignoring the reign of terror perpetuated by the Ku Klux Klan and the White Citizens Council, limits racial injustice to individual acts of meanness.

We respect the stellar performances of the African American actresses in this film. Indeed, this statement is in no way a criticism of their talent. It is, however, an attempt to provide context for this popular rendition of black life in the Jim Crow South. In the end, The Help is not a story about the millions of hardworking and dignified black women who labored in white homes to support their families and communities. Rather, it is the coming-of-age story of a white protagonist, who uses myths about the lives of black women to make sense of her own. The Association of Black Women Historians finds it unacceptable for either this book or this film to strip black women’s lives of historical accuracy for the sake of entertainment.

Ida E. Jones is National Director of ABWH and Assistant Curator at Howard University. Daina Ramey Berry, Tiffany M. Gill, and Kali Nicole Gross are Lifetime Members of ABWH and Associate Professors at the University of Texas at Austin. Janice Sumler-Edmond is a Lifetime Member of ABWH and is a Professor at Huston-Tillotson University.

Word Count: 766

Suggested Reading:

Fiction:

Like one of the Family: Conversations from A Domestic’s Life, Alice Childress

The Book of the Night Women by Marlon James

Blanche on the Lam by Barbara Neeley

The Street by Ann Petry

A Million Nightingales by Susan Straight

Non-Fiction:

Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household by Thavolia Glymph

To Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors by Tera Hunter

Labor of Love Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family, from Slavery to the Present by Jacqueline Jones

Living In, Living Out: African American Domestics and the Great Migration by Elizabeth Clark-Lewis

Coming of Age in Mississippi by Anne Moody

Any questions, comments, or interview requests can be sent to: ABWHTheHelp@gmail.com

ABWH Statement The Help (pdf) pdf button

Friday, December 02, 2011

Have You Heard of the National Defense Authorization Act?

This is worse than the Violent Radicalization and Homegrown Terrorism Act.Passed by the U.S. Senate, but thankfully facing a veto from President Obama, this bill truly would erode every right of every citizen in the United States. Read here .

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

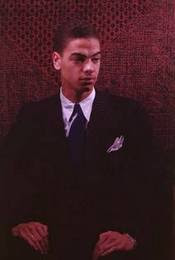

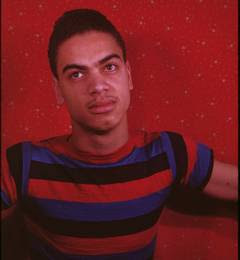

Black Like Jesus: A Photo-Interview with Thomas Sayers Ellis

Thomas Sayers Ellis is one of the premier African American poets in the United States today as well as a distinguished college professor who teaches at both Sarah Lawrence College and Lesley University. A founder of the Dark Room Collective,a writer's collective that produced many of today's notable Afro-American writers, Ellis has won numerous honors and awards and is a contributing editor for the prestigious journal, Callaloo. Ellis won the Whiting Writer's Award in 2005 and the John C. Zacharis First Book Award in 2006. Mr. Ellis is also a photographer. Three of his pieces are included in this interview. Recently, I contacted him and asked him if he would like to conduct an interview with JuliusSpeaks, an idea which he enthusiastically endorsed. The following is what transpired.

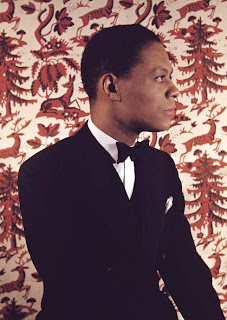

Gentrification Is Dangerous, TSE 1986

1. Tell us something of your background. Where are you from? Are you married? Family?

I am from Washington, D.C. and many of the facts of my life are in my poems, real and imagined. I am not married in the same way that I am not metaphor. I am not single because poet means plural, a collective process and many collective utterances. I do think that it’s too bad that the places we are ‘’from” have to stay in one place forever. Yes, I wish land, the notion of local, were more mobile. Prosody, prose and song, must move.

2. What inspired you to become a poet?

I don’t think I was ever inspired to be one, but I am sure there were a great many other things that I could not be, so many so that poet was there waiting. It was always there––in the widest way. I was never without the possibility of it. I was full of it before I was anything else. At a very early age I was chased in my dreams and in my play by images and sound. A new definition of inspiration: the day images and sound caught me.

3. What does it mean to you to be a person of color and an artist in the United States at this time?

It means too many things to write but I am a Black writer in America and that means that I am Black and American, a double strengthened force, not an America who has been weakened or burdened by Blackness. Blackness adds range and elasticity to my American-ness. The task, however, is to write poems that continue language and poems that do not need the wave of time to become pertinent to readers. The struggle is to “live now” and to be relevant now, to look forward-back, and not backward-forward. We non white poets must also do a better job at defending our organic aesthetic handbooks. Too often those of us who don’t walk the way (in our lines) of academic logic get left out. Now is the time to make room for a vaster range of intelligences, triflin’ and proper.

4. You seem to be very aware of your audience. Do you have a target audience that you approach through your poetry? What is the audience that reads you?

I really am only aware of ears and there are too many of them to target. I approach each poem trying only to satisfy it, the poem. I hear it with my ears. We know poets read poets, mostly, and anyone else is extra. I try not to think about anything but the language and I am often also working against the poem being “about” a thing or one thing, but I always fail at that. There is something about English that traps you in the land of about which leads you to target by use of subject. Traditionally, a poem about Race has an audience and a poem about avocados has another audience. All I want is wholeness, for both audiences to come together and come apart in my odd body-toolbox, but only when I want wholeness.

5. You seem to play a lot with language in your poetry. Do you have a background in linguistics or philology?

No, but I am sensitive to the edges and insides and connotations and denotations of words. I believe in the syllabic integrity of every body part of every word. The front of a word is just as important as the end of a word, and the middle where the vowels often hide is both sonic and creamy. It may be fair to say that I have a front-ground in listening and that I am constantly trying to unlearn feeling.

6. Do you consider the technique and construction of a poem more important than the essence or the delivery?

I believe in Equality.

The Creative Process is the original Religion.

Poetry (not the poem) is

the echo of prayer.

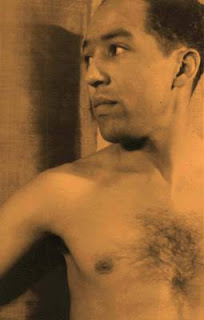

Brown Girl,Brown Church, TSE 2011

7. Explain your approach to poetry- both in its written form and in regards to performance.

I sit down, in surrender, when I write.

I stand up, in triumph, when I read.

First I crawl

then I perform-a-form.

Must be the dog in me.

8. What would you say is the state of poetry in America today? Is there a vibrant poetry scene to be found? Is there innovation?

There is not a state of…

Poetry can’t be mapped

or polled or even populated.

The moment it vibrates

or nears “vibrant”

it becomes a disaster and people call FEMA.

It invents loss

but no one wants

to know that,

what, that earthquakes

are innovative.

9. How would you define yourself as a social and political being?

I signify one step ahead of those who gentrify aka my Party has not begun. It ain't late enough yet and the music ain't loud enough yet. Quietly poetry pumps up the volume!

10. The poem "Sticks" seems to be your most personal poem. Your poetry, unlike some others, does not reflect a lot of you in it. Why is that?

“All art is autobiographical.” I think Vincent van Gogh said that.

I am there, in the work and all over it. Americans are just lousy at reading nonlinear behavior in writing. I am there but not in the easy costumed way of “Confession.” A poem has to be visual and lyric but not necessarily a secretary to reality, or solely a service to experience. I would like to give the reader a reading experience that has its own breathing walk. Reader, surrender.

11. What is next for you?

It would be nice to turn my back on me or to meet me before “next.” I am going to try to be before me. I feel like my “next” has already happened and now I am going to spend some time running in the other direction ––away from intelligence, toward…

Black Like Jesus, TSE 2011

Thanks for this interview. It was a pleasure.

Gentrification Is Dangerous, TSE 1986

1. Tell us something of your background. Where are you from? Are you married? Family?

I am from Washington, D.C. and many of the facts of my life are in my poems, real and imagined. I am not married in the same way that I am not metaphor. I am not single because poet means plural, a collective process and many collective utterances. I do think that it’s too bad that the places we are ‘’from” have to stay in one place forever. Yes, I wish land, the notion of local, were more mobile. Prosody, prose and song, must move.

2. What inspired you to become a poet?

I don’t think I was ever inspired to be one, but I am sure there were a great many other things that I could not be, so many so that poet was there waiting. It was always there––in the widest way. I was never without the possibility of it. I was full of it before I was anything else. At a very early age I was chased in my dreams and in my play by images and sound. A new definition of inspiration: the day images and sound caught me.

3. What does it mean to you to be a person of color and an artist in the United States at this time?

It means too many things to write but I am a Black writer in America and that means that I am Black and American, a double strengthened force, not an America who has been weakened or burdened by Blackness. Blackness adds range and elasticity to my American-ness. The task, however, is to write poems that continue language and poems that do not need the wave of time to become pertinent to readers. The struggle is to “live now” and to be relevant now, to look forward-back, and not backward-forward. We non white poets must also do a better job at defending our organic aesthetic handbooks. Too often those of us who don’t walk the way (in our lines) of academic logic get left out. Now is the time to make room for a vaster range of intelligences, triflin’ and proper.

4. You seem to be very aware of your audience. Do you have a target audience that you approach through your poetry? What is the audience that reads you?

I really am only aware of ears and there are too many of them to target. I approach each poem trying only to satisfy it, the poem. I hear it with my ears. We know poets read poets, mostly, and anyone else is extra. I try not to think about anything but the language and I am often also working against the poem being “about” a thing or one thing, but I always fail at that. There is something about English that traps you in the land of about which leads you to target by use of subject. Traditionally, a poem about Race has an audience and a poem about avocados has another audience. All I want is wholeness, for both audiences to come together and come apart in my odd body-toolbox, but only when I want wholeness.

5. You seem to play a lot with language in your poetry. Do you have a background in linguistics or philology?

No, but I am sensitive to the edges and insides and connotations and denotations of words. I believe in the syllabic integrity of every body part of every word. The front of a word is just as important as the end of a word, and the middle where the vowels often hide is both sonic and creamy. It may be fair to say that I have a front-ground in listening and that I am constantly trying to unlearn feeling.

6. Do you consider the technique and construction of a poem more important than the essence or the delivery?

I believe in Equality.

The Creative Process is the original Religion.

Poetry (not the poem) is

the echo of prayer.

Brown Girl,Brown Church, TSE 2011

7. Explain your approach to poetry- both in its written form and in regards to performance.

I sit down, in surrender, when I write.

I stand up, in triumph, when I read.

First I crawl

then I perform-a-form.

Must be the dog in me.

8. What would you say is the state of poetry in America today? Is there a vibrant poetry scene to be found? Is there innovation?

There is not a state of…

Poetry can’t be mapped

or polled or even populated.

The moment it vibrates

or nears “vibrant”

it becomes a disaster and people call FEMA.

It invents loss

but no one wants

to know that,

what, that earthquakes

are innovative.

9. How would you define yourself as a social and political being?

I signify one step ahead of those who gentrify aka my Party has not begun. It ain't late enough yet and the music ain't loud enough yet. Quietly poetry pumps up the volume!

10. The poem "Sticks" seems to be your most personal poem. Your poetry, unlike some others, does not reflect a lot of you in it. Why is that?

“All art is autobiographical.” I think Vincent van Gogh said that.

I am there, in the work and all over it. Americans are just lousy at reading nonlinear behavior in writing. I am there but not in the easy costumed way of “Confession.” A poem has to be visual and lyric but not necessarily a secretary to reality, or solely a service to experience. I would like to give the reader a reading experience that has its own breathing walk. Reader, surrender.

11. What is next for you?

It would be nice to turn my back on me or to meet me before “next.” I am going to try to be before me. I feel like my “next” has already happened and now I am going to spend some time running in the other direction ––away from intelligence, toward…

Black Like Jesus, TSE 2011

Thanks for this interview. It was a pleasure.

Tuesday, November 08, 2011

Sunday, November 06, 2011

Save Jimmy Baldwin's House

A call has been sent out recently to help save and preserve Jimmy Baldwin's house in the south of France. Here are some images of that beautiful house.

Tuesday, November 01, 2011

Friday, October 28, 2011

Saturday, October 22, 2011

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

A Powerful Article in Tribute to E. Lynn Harris Written by L. Michael Gipson

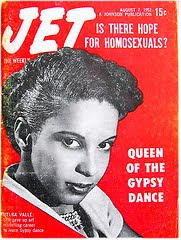

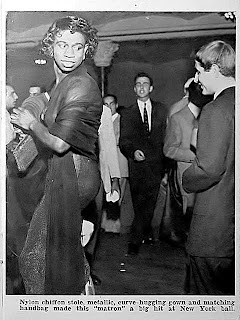

On July 24, 2009, E. Lynn Harris went into cardiac arrest and died at the age of 54 years old. Lynn, as he was known to friends and associates, was a 10 time New York Times bestselling author with over 4 million books in print. This distinction made E. Lynn Harris the first commercially successful, openly Black gay writer in America since James Baldwin. While he stood on the shoulders of a spare number of pioneering Black gay writers who came before him, including: Essex Hemphill, Joseph Beam, Assoto Saint, Yulisa Amadu Maddy, Wallace Thurman, Richard Bruce Nugent, Samuel R. Delaney and other members of this exclusive club, Lynn would go further than any of them in cultural impact and financial reward. Like Harris, all of these writers described the lives of closeted and openly gay Black men, some long before Harris was even born, but Harris fortuitously arrived at a time when the culture was hungry for different, more sophisticated stories about Black people. The public proved eager for operatic tales of Black affluence, celebrity success, and salacious sexual diversities, not the previously dominating stories of poverty, racial animus or traditional sexual and family relations. For them, Lynn delivered, changing the national dialogue about Black gay men forever.

The debut of Invisible Life and its numerous sequels benefited as much from the times as it did from the earnestness of Harris’s fresh, confessional tales of closeted Black male life on the down low. In 1991, when Harris arrived on the scene, America was in the middle of its fourth Black literary renaissance, only this one was better known for its commercial achievement rather than its literary cred. In the late 80s, early 90s, mainstream publishers (again) discovered that Black people do indeed read books and were a considerably large portion of the untapped literary market. The stratospheric success of Terry McMillan’s Waiting To Exhale proved prescient, shepherding in an explosion of Black writers delivering what some derisively be termed “sistah girl fiction” and the vaguely dismissive “urban lit” by others. Simultaneously, Hollywood realized (again) there was an untapped market for urban romantic comedies starring post-Civil Rights buppies in situations parallel to their professional white counterparts. Popular music was just experiencing its split between b-boy rappers and thug crooners and those “queer-oriented” dance music artists like RuPaul, C.C. Penniston, C&C Music Factory, and Crystal Waters whose tribal beats were fostering a revival of the sexually diverse discotheque. In these anything goes nightclubs, straights and gays and everything in between together partied like it was 1999 and tried to live out try-sexual movies like Threesome. The organized gay rights movements were becoming more vocal and visible, but thanks in part to queer racism, was largely a white identified movement. Black gay life was limited to bars, gyms, clubs, parks, bathhouses, fraternities and telephone chatlines—there was no Internet and you could count the national number of Black gay organizations on your hands.

Then came E. Lynn Harris, a former IBM executive, telling stories that married all the energy of the roaring 90s for Blacks: the gay nightlife, the dual lives of closeted men, neo-Black bougie life from fraternities to boardrooms, the pressures and ambitions of instant millionaire artists and athletes in the entertainment industry, all without the specter of racism and only the occasional touchstone about AIDS. Lynn fed readers a sepia-colored Dynasty with all the camp, family melodrama, and delightful sexual triangles and quadrangles still intact and little of the harsher realities of poor and working class Black gay lives.

By ensuring parallel Black straight love stories were formulaically included in nearly every novel and initially marketing them to Black beauty salons, Harris got Black women readerships’ attention and kept it. Almost overnight Black women were aware of the existence of Black homosexuality beyond the stereotypical Blaine and Merriweather from the Men on Film skits from the then uber-popular In Living Color. Before J.L. King’s memoir, before Oprah Winfrey’s infamous D.L. Men’s Show, before Terry McMillan was bamboozled by her bisexual hubby, Jonathan Plummer, there was Harris educating millions about a phenomenon centuries old. It seems laughable today, but when Harris first lifted the veil, some Black women were completely stunned to learn that their man could love sports, drink beer, be fit, be sexy, be successful, speak in baritones, and exercise complete control of his wrists and still like, love and lust after men. Before Lynn, this shadow society of men was a whispered secret between some urbanite gay men and their straight girlfriends, and even then there was a sense among these women that their gay friends were exaggerating the scale of heterosexually identified men who chased after them (and not necessarily the other way around). But all of that was before Lynn. With books, stage plays and musicals, and several forthcoming movies of his work, Lynn changed everything.

After Lynn, Black male heterosexuality is less likely to be automatically assumed based on masculine presentation. After Lynn, many Black heterosexual men who were not on the D.L. resented the implication that they could harbor same sex desires, assisting some in embracing hyper-masculinity as a distancing response. After Lynn, the conversation about HIV/AIDS shifted and black women realized that a wedding ring would not protect them from a pandemic. After Lynn, there was an unscientifically founded belief that gay men and their DL lovers were primarily responsible for the precipitous rise of HIV among Black women, a myth repeatedly proven false by the Centers for Disease Control. After Lynn, Black women and some Black straight men realized that they had more in common with their Black gay brethren than they didn’t and began to dialogue with their gay brothers as people, not as a social problem. After Lynn, Black women realized Black gay men weren’t dismissible freaks, but competition and willing accomplices in their husbands and boyfriends infidelities—causing rifts and suspicion. After Lynn, Black gay youth no longer had to read white gay or Black straight fiction to identify a broad range of well-packaged reflections of their racial and sexual identity, both “out” and closeted. After Lynn, Black gay youth would see those reflections as romantically high bars of idealized male beauty, ostentatious wealth, preternatural talents, academic superiority, and bourgeoisie values coupled with wavering morality on participation in marital duplicity and infidelity. After Lynn, Black gay writers write and publish often, laudably believing their much needed voices are viable, valuable and marketable—regardless of literary quality. After Lynn, no publishing house could ever reject another Black gay writers’ stories as commercial suicide and be taken seriously. After Lynn, no one could say that Black gay and bisexual men didn’t exist and weren’t indeed vibrantly alive, and ever be taken seriously. Flaws and all, positive and negative, E. Lynn Harris changed American views, perspective and conversation, about Black gay men forever. And for that I thank my dear, sweet associate of fifteen years. May he rest in peace.

The debut of Invisible Life and its numerous sequels benefited as much from the times as it did from the earnestness of Harris’s fresh, confessional tales of closeted Black male life on the down low. In 1991, when Harris arrived on the scene, America was in the middle of its fourth Black literary renaissance, only this one was better known for its commercial achievement rather than its literary cred. In the late 80s, early 90s, mainstream publishers (again) discovered that Black people do indeed read books and were a considerably large portion of the untapped literary market. The stratospheric success of Terry McMillan’s Waiting To Exhale proved prescient, shepherding in an explosion of Black writers delivering what some derisively be termed “sistah girl fiction” and the vaguely dismissive “urban lit” by others. Simultaneously, Hollywood realized (again) there was an untapped market for urban romantic comedies starring post-Civil Rights buppies in situations parallel to their professional white counterparts. Popular music was just experiencing its split between b-boy rappers and thug crooners and those “queer-oriented” dance music artists like RuPaul, C.C. Penniston, C&C Music Factory, and Crystal Waters whose tribal beats were fostering a revival of the sexually diverse discotheque. In these anything goes nightclubs, straights and gays and everything in between together partied like it was 1999 and tried to live out try-sexual movies like Threesome. The organized gay rights movements were becoming more vocal and visible, but thanks in part to queer racism, was largely a white identified movement. Black gay life was limited to bars, gyms, clubs, parks, bathhouses, fraternities and telephone chatlines—there was no Internet and you could count the national number of Black gay organizations on your hands.

Then came E. Lynn Harris, a former IBM executive, telling stories that married all the energy of the roaring 90s for Blacks: the gay nightlife, the dual lives of closeted men, neo-Black bougie life from fraternities to boardrooms, the pressures and ambitions of instant millionaire artists and athletes in the entertainment industry, all without the specter of racism and only the occasional touchstone about AIDS. Lynn fed readers a sepia-colored Dynasty with all the camp, family melodrama, and delightful sexual triangles and quadrangles still intact and little of the harsher realities of poor and working class Black gay lives.

By ensuring parallel Black straight love stories were formulaically included in nearly every novel and initially marketing them to Black beauty salons, Harris got Black women readerships’ attention and kept it. Almost overnight Black women were aware of the existence of Black homosexuality beyond the stereotypical Blaine and Merriweather from the Men on Film skits from the then uber-popular In Living Color. Before J.L. King’s memoir, before Oprah Winfrey’s infamous D.L. Men’s Show, before Terry McMillan was bamboozled by her bisexual hubby, Jonathan Plummer, there was Harris educating millions about a phenomenon centuries old. It seems laughable today, but when Harris first lifted the veil, some Black women were completely stunned to learn that their man could love sports, drink beer, be fit, be sexy, be successful, speak in baritones, and exercise complete control of his wrists and still like, love and lust after men. Before Lynn, this shadow society of men was a whispered secret between some urbanite gay men and their straight girlfriends, and even then there was a sense among these women that their gay friends were exaggerating the scale of heterosexually identified men who chased after them (and not necessarily the other way around). But all of that was before Lynn. With books, stage plays and musicals, and several forthcoming movies of his work, Lynn changed everything.

After Lynn, Black male heterosexuality is less likely to be automatically assumed based on masculine presentation. After Lynn, many Black heterosexual men who were not on the D.L. resented the implication that they could harbor same sex desires, assisting some in embracing hyper-masculinity as a distancing response. After Lynn, the conversation about HIV/AIDS shifted and black women realized that a wedding ring would not protect them from a pandemic. After Lynn, there was an unscientifically founded belief that gay men and their DL lovers were primarily responsible for the precipitous rise of HIV among Black women, a myth repeatedly proven false by the Centers for Disease Control. After Lynn, Black women and some Black straight men realized that they had more in common with their Black gay brethren than they didn’t and began to dialogue with their gay brothers as people, not as a social problem. After Lynn, Black women realized Black gay men weren’t dismissible freaks, but competition and willing accomplices in their husbands and boyfriends infidelities—causing rifts and suspicion. After Lynn, Black gay youth no longer had to read white gay or Black straight fiction to identify a broad range of well-packaged reflections of their racial and sexual identity, both “out” and closeted. After Lynn, Black gay youth would see those reflections as romantically high bars of idealized male beauty, ostentatious wealth, preternatural talents, academic superiority, and bourgeoisie values coupled with wavering morality on participation in marital duplicity and infidelity. After Lynn, Black gay writers write and publish often, laudably believing their much needed voices are viable, valuable and marketable—regardless of literary quality. After Lynn, no publishing house could ever reject another Black gay writers’ stories as commercial suicide and be taken seriously. After Lynn, no one could say that Black gay and bisexual men didn’t exist and weren’t indeed vibrantly alive, and ever be taken seriously. Flaws and all, positive and negative, E. Lynn Harris changed American views, perspective and conversation, about Black gay men forever. And for that I thank my dear, sweet associate of fifteen years. May he rest in peace.

Saturday, October 08, 2011

Listening to Whitney Houston On My Way Home This Evening

On my way home this evening, Whitney Houston's version of "I Will Always Love You" came on the radio and took me aback a bit as I listened to the clear, crisp, and magnificent voice that delivered each powerful note of the song. It was Whitney at her best. and it started me to thinking about Ms. Houston, her remarkable talent, and her gold-dusted career that has seen such highs and such lows as she could once reach with that magnificent range of hers. Undoubtedly, Whitney Houston is the best female vocalist of her generation. No one could even compete with her vocal range, her vocal mastery, And she still holds court as one of the best-selling female recording artists of all time.

When Whitney started out in the early eighties, following her brief, Afrocentric moment at her debut when on the

cover of the album she sported a fade, Clive Davis and the rest of her team worked hard to produce the Whitney magic and introduced her onto the pop scene as the quintessential Black Barbie doll. Oh, she wanted to dance with somebody.... and her outfit was replete with big hair and leggings that read very middle class and feminine. The consuming public LOVED it and in no time she had carved her niche inside the music industry and was accepted as a pop princess holding her own against the likes of Madonna and even finding herself on MTV, one of the few Black artists who did at the time. For more than a decade after that, Whitney was THE most prominent Black female singer in the world. Her superstar status was cemented in 1992 with The Bodyguard. The film, crafted personally for her out of a 1970s chucked vehicle for Diana Ross and Steve McQueen, cemented her reputation as a movie star, shelling in over $400 million dollars at the box office, making it one of the most successful films of the time. The soundtrack coinciding with the film, also called The Bodygaurd, debuted at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 setting a record at fourteen weeks in that position and went seventeen times platinum, landing it as the best selling soundtrack of all time.

There is something to be said about girls, and particularly about Black girls, from good, middle class homes who are always fixated with thugs/bad boys/ and generally unwholesome and unsavory figures. Although Whitney had been using drugs ever since the beginning of her career probably, her downfall started when she met and married Bobby Brown. I, for one, believe everything she told Oprah. She was totally committed to Bobby(good girl syndrome-trained well by her mama) and subsequently they spent a lot of days in bed snorting and shooting and watching TV. Although, though this explains her loss of control over her career( didn't mama at one point take over her finances with a court order ala Natalie Cole?) , by no means does this account for her loss of voice. I, for one, was quite befuddled over the entire brouhaha about Whitney's losing her voice. Everyone was speculating--drugs, Bobby, stress, etc, etc.. I think not. I think more it runs in the genes....It seemed no one remembered it wasnt that long ago people were yelling "Hey Dionne, sit down and shut up, please!" I wasn't surprised at all. Fortunately for Whitney, her legacy is already set....I just hope she can spare herself more embarrassing moments and that, if all she can find is the thug or the bad boy type, that she chooses to remain single for the rest of her .life.

Friday, October 07, 2011

My Faith Has Been Renewed: Michelle Obama, Our First Lady, Is a Wonderful Leader

In this month's issue of Ebony, First Lady Michelle Obama renewed my faith when she spoke with Kevin Chappell about the power of movements. She said, "nothing is ever built in a day. The only thing that happens in an instant is destruction...Build something...earthquake; it's gone. But everything else requires time....Don't let the struggle discourage you because it's hard. It's supposed to be hard." As an example, she spoke of Nelson Mandela, whom she just visited with in South Africa. "There must have been moments in that jail when he (Mandela) thought, ' This is never going to work,,' but if we see Mandela as hope, we would see the slowness not as a reason to stop and be impatient but to keep moving and not get so caught up in the immediacy." Bless you, Michelle Obama....

Thursday, October 06, 2011

Community Healing Days--Listen Up Black People

October 15-17 are Community Healing Days

We’re coming up on an annual celebration that not everyone is familiar with, but is tremendously important to the Black community.

It’s called Community Healing Days, a three day period on the third weekend of every October designed to focus Black people on eliminating the tired, but powerful, myth of black inferiority. The celebration is sponsored by the Community Healing Network and championed by Dr. Maya Angelou.

This year, on October 15, 16 and 17, Dr. Angelou is asking folks to wear something sky blue during Community Healing Days to show “our collective determination to turn the pain of the blues into the sky blue of unlimited possibilities.” That’s right, Sky-Blue, like the beautiful, limitless sky above, a reflection of the positive way we need to view ourselves.

But unfortunately –for many African Americans– how we view ourselves is a byproduct of how others view us. Case in point. In the compelling new book entitled Whistling Vivaldi by psychologist Claude Steele, he references a scenario involving an African American journalist and former grad student at the University of Chicago.

As a student walking down the street in his Hyde Park neighborhood each evening, he would see white folk either clutch their belongings or each other, stare straight ahead, or switch to the other side of the street. Noting that white people were “frightened to death of him,” the young man internalized this treatment and began taking side streets to avoid making his white neighbors fearful or uncomfortable.

Eventually he stopped doing this after he noticed that whenever he whistled as he walked–especially tunes by classical composers like Vivaldi—his white neighbors would treat him differently. Some would even smile at him.

Psychologists reason that whites figured that if this guy knows Vivaldi, he must be okay. The point here is that we sometimes begin to behave in a way that responds to stereotypes.

It speaks both to the sickness in our society and, more importantly, in this case, to the sickness in us. When we start pretending – acting in ways that play into what others think or expect of us, then the sickness is no longer their’s… it becomes ours.

Think about the stereotypes that suggest young black males are criminals, or can’t do well in math… how young black girls are merely video vixens, or can’t do well in science.

You see, when media and society peddle stereotypes –especially those inaccurately characterizing our impressionable youth and children—the damage is both serious and real not just because of the sick folks promoting them, but because of those growing sicker every day by receiving, emulating and perpetuating them.

That’s the thing about stereotypes. They start out as mostly false statements but gain steam if not challenged immediately, and ultimately gain credibility when perpetuated by its victims. The fact is that media and society have been peddling stereotypes about us for centuries.

In Whistling Vivaldi, Steele shows how stereotypes affect our perceptions of ourselves and influence how we act in certain situations, be they professional, academic or personal. As a people, we need to be intentional about overcoming the negative stereotypes about who we are and what we can do. Especially for our children — we need to positively affirm our self-worth, our accomplishments and our beauty to combat those stereotypes and ensure we are defining and viewing ourselves positively.

This is what Community Healing Days is all about. And that ain’t just Whistlin’ Vivaldi.

So let’s be sure to celebrate Community Healing Days – in our sky blue – on October 15th through 17th. You can get more info on this at communityhealingnet.org

Stephanie Robinson is President and CEO of The Jamestown Project, a national think tank focused on democracy. She is an author, a Lecturer on Law at the Harvard Law School and former Chief Counsel to the late Senator Edward M. Kennedy. Stephanie reaches 8 to 10 million listeners each week as political commentator for the popular radio venue, The Tom Joyner Morning Show. Visit her online at www.StephanieRobinsonSpeaks.com

Monday, October 03, 2011

Rick Perry's Niggerhead

Looking at the different components that come together to make up a person will always provide a key to that person's personality and perspective. The idea that Perry's white, privileged family would name their hunting lodge Niggerhead speaks to where they fit socially, politically, culturally. One has to ask did he not think this might cause problems for him if he chose to run for president as he did not even attempt to hide this knowledge--which either spells carelessness or a lack of concern on his part. What part of this man and his background do we want in the white house? Only those wishing for a clear return of white male capitalist patriarchy would even think that Perry, with his track record, would be suitable to lead such a huge, diverse nation such as this. Meanwhile, I wonder when was the last time a soiree was held at Niggerhead?

Sunday, October 02, 2011

Saturday, October 01, 2011

My Life and My Direction

Ever since I was very young, my ambitious brain had two goals which were absolute amongst everything else. I would trailblaze Barbra Streisand's path, only in my own way, and be a famed and published writer by the time I was nineteen. I also was going to get my doctorate by the time I was thirty, because I wanted to be Angela Davis(as much as I could be). However, my reasonings for all of these things were quite something else. Oh the joys of a young Black boy wanting to emulate Barbra! Major differences...but still I bask in the light of Barbra. In terms of my doctorate, I will get it one day. As I have thought on it, at first my reasoning for wanting a doctorate was two fold: One, I like to learn, and on that point I will still attain a doctorate (sooner rather than later), but secondly, I was trying to compete with my ancestors, who were all educators, filigreed and degreed--wanting to best them one by doing something like I will not only get my doctorate but I can be Angela Davis too! Well, I have since figured that my ancestors have one up on me...they have the benefit of being dead and no longer here....I can take my time.... All of that said, I will be published very soon, and will start that merciless process of phd applications....but will do it in my own way and in my own time.....because I will not be rushed....

Monday, September 26, 2011

Open Letter to Angela Davis from James Baldwin: From One Powerful Icont to Another

A Y. Davis

by James Baldwin

Dear Sister:

One might have hoped that, by this hour, the very sight of chains on Black flesh, or the very sight of chains, would be so intolerable a sight for the American people, and so unbearable a memory, that they would themselves spontaneously rise up and strike off the manacles. But, no, they appear to glory in their chains; now, more than ever, they appear to measure their safety in chains and corpses. And so, Newsweek, civilized defender of the indefensible, attempts to drown you in a sea of crocodile tears ("it remained to be seen what sort of personal liberation she had achieved") and puts you on its cover, chained.

You look exceedingly alone—as alone, say, as the Jewish housewife in the boxcar headed for Dachau, or as any one of our ancestors, chained together in the name of Jesus, headed for a Christian land.

Well. Since we live in an age which silence is not only criminal but suicidal, I have been making as much noise as I can, here in Europe, on radio and television—in fact, have just returned from a land, Germany, which was made notorious by a silent majority not so very long ago. I was asked to speak on the case of Miss Angela Davis, and did so. Very probably an exerciser in futility, but one must let no opportunity slide.

I am something like twenty years older than you, of that generation, therefore, of which George Jackson ventures that "there are no healthy brothers—none at all." I am in no way equipped to dispute this speculation (not, anyway, without descending into what, at the moment, would be irrelevant subtleties) for I know too well what he means. My own state of health is certainly precarious enough. In considering you, and Huey, and George and (especially) Jonathan Jackson, I began to apprehend what you may have had in mind when you spoke of the uses to which we could put the experience of the slave. What has happened, it seems to me, and to put it far too simply, is that a whole new generation of people have assessed and absorbed their history, and, in that tremendous action, have freed themselves of it and will never be victims again. This may seem an odd, indefensibly pertinent and insensitive thing to say to a sister in prison, battling for her life—for all our lives. Yet, I dare to say it, for I think you will perhaps not misunderstand me, and I do not say it, after all, from the position of spectator.

I am trying to suggest that you—for example—do not appear to be your father's daughter in the same way that I am my father's son. At bottom, my father's expectations and mine were the same, the expectations of his generation and mine were the same; and neither the immense difference in our ages nor the move from the South to the North could alter these expectations or make our lives more viable. For, in fact, to use the brutal parlance of that hour, the interior language of despair, he was just a n-----—a n----- laborer preacher, and so was I. I jumped the track but that's of no more importance here, in itself, than the fact that some poor Spaniards become rich bull fighters, or that some poor Black boys become rich—boxers, for example. That's rarely, if ever, afforded the people more than a great emotional catharsis, though I don't mean to be condescending about that, either. But when Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali and refused to put on that uniform (and sacrificed all that money!) a very different impact was made on the people and a very different kind of instruction had begun.

The American triumph—in which the American tragedy has always been implicit—was to make Black people despise themselves. When I was little I despised myself; I did not know any better. And this meant, albeit unconsciously, or against my will, or in great pain, that I also despised my father. And my mother. And my brothers. And my sisters. Black people were killing each other every Saturday night out on Lenox Avenue, when I was growing up; and no one explained to them, or to me, that it was intended that they should; that they were penned where they were, like animals, in order that they should consider themselves no better than animals. Everything supported this sense of reality, nothing denied it: and so one was ready, when it came time to go to work, to be treated as a slave. So one was ready, when human terrors came, to bow before a white God and beg Jesus for salvation—this same white God who was unable to raise a finger to do so little as to help you pay your rent, unable to be awakened in time to help you save your child!

There is always, of course, more to any picture than can speedily be perceived and in all of this—groaning and moaning, watching, calculating, clowning, surviving, and outwitting, some tremendous strength was nevertheless being forged, which is part of our legacy today. But that particular aspect of our journey now begins to be behind us. The secret is out: we are men!

But the blunt, open articulation of this secret has frightened the nation to death. i wish I could say, "to life," but that is much to demand of a disparate collection of displaced people still cowering in their wagon trains and singing "Onward Christian Soldiers." The nation, if America is a nation, is not in the least prepared for this day. It is a day which the Americans never expected to see, however piously they may declare their belief in progress and democracy. Those words, now, on American lips, have become a kind of universal obscenity: for this most unhappy people, strong believers in arithmetic, never expected to be confronted with the algebra of their history.

One way of gauging a nation's health, or of discerning what it really considers to be its interests—or to what extent it can be considered as a nation as distinguished from a coalition of special interests—is to examine those people it elects to represent or protect it. One glance at the American leaders (or figureheads) conveys that America is on the edge of absolute chaos, and also suggests the future to which American interests, if not the bulk of the American people, appear willing to consign the Blacks. (Indeed, one look at our past conveys that.) It is clear that for the bulk of our (nominal) countrymen, we are all expendable. And Messrs. Nixon, Agnew, Mitchell, and Hoover, to say nothing, of course, of the Kings' Row basket case, the winning Ronnie Reagan, will not hesitate for an instant to carry out what they insist is the will of the people.

But what, in America, is the will of the people? And who, for the above-named, are the people? The people, whoever they may be, know as much about the forces which have placed the above-named gentlemen in power as they do about the forces responsible for the slaughter in Vietnam. The will of the people, in America, has always been at the mercy of an ignorance not merely phenomenal, but sacred, and sacredly cultivated: the better to be used by a carnivorous economy which democratically slaughters and victimizes whites and Blacks alike. But most white Americans do not dare admit this (though they suspect it) and this fact contains mortal danger for the Blacks and tragedy for the nation.

Or, to put it another way, as long as white Americans take refuge in their whiteness—for so long as they are unable to walk out of this most monstrous of traps—they will allow millions of people to be slaughtered in their name, and will be manipulated into and surrender themselves to what they will think of—and justify—as a racial war. They will never, so long as their whiteness puts so sinister a distance between themselves and their own experience and the experience of others, feel themselves sufficiently human, sufficiently worthwhile, to become responsible for themselves, their leaders, their country, their children, or their fate. They will perish (as we once put it in our black church) in their sins —that is, in their delusions. And this is happening, needless to say, already, all around us.

Only a handful of the millions of people in this vast place are aware that the fate intended for you, Sister Angela, and for George Jackson, and for the numberless prisoners in our concentration camps—for that is what they are—is a fate which is about to engulf them, too, White lives, for the forces which rule in this country, are no more sacred than Black ones, as many and many a student is discovering, as the white American corpses in Vietnam prove. If the American people are unable to contend with their elected leaders for the redemption of their own honor and the loves of their own children, we the Blacks, the most rejected of the Western children, can expect very little help at their hands; which, after all, is nothing new. What the Americans do not realize is that a war between brothers, in the same cities, on the same soil is not a racial war but a civil war. But the American delusion is not only that their brothers all are white but that the whites are all their brothers.

So be it. We cannot awaken this sleeper, and God knows we have tried. We must do what we can do, and fortify and save each other—we are not drowning in an apathetic self-contempt, we do feel ourselves sufficiently worthwhile to contend even with the inexorable forces in order to change our fate and the fate of our children and the condition of the world! We know that a man is not a thing and is not to be placed at the mercy of things. We know that air and water belong to all mankind and not merely to industrialists. We know that a baby does not come into the world merely to be the instrument of someone else's profit. We know that a democracy does not mean the coercion of all into a deadly—and, finally, wicked— mediocrity but the liberty for all to aspire to the best that is in him, or that has ever been.

We know that we, the Blacks, and not only we, the blacks, have been, and are, the victims of a system whose only fuel is greed, whose only god is profit. We know that the fruits of this system have been ignorance, despair, and death, and we know that the system is doomed because the world can no longer afford it—if, indeed, it ever could have. And we know that, for the perpetuation of this system, we have all been mercilessly brutalized, and have been told nothing but lies, lies about ourselves and our kinsmen and our past, and about love, life, and death, so that both soul and body have been bound in hell.

The enormous revolution in black consciousness which has occurred in your generation, my dear sister, means the beginning or the end of America. Some of us, white and Black, know how great a price has already been paid to bring into existence a new consciousness, a new people, an unprecendented nation. If we know, and do nothing, we are worse than the murderers hired in our name.

If we know, then we must fight for your life as though it were our own—which it is—and render impassable with our bodies the corridor to the gas chamber. For, if they take you in the morning, they will be coming for us that night.

Therefore: peace.

Brother James

November 19, 1970

by James Baldwin

Dear Sister:

One might have hoped that, by this hour, the very sight of chains on Black flesh, or the very sight of chains, would be so intolerable a sight for the American people, and so unbearable a memory, that they would themselves spontaneously rise up and strike off the manacles. But, no, they appear to glory in their chains; now, more than ever, they appear to measure their safety in chains and corpses. And so, Newsweek, civilized defender of the indefensible, attempts to drown you in a sea of crocodile tears ("it remained to be seen what sort of personal liberation she had achieved") and puts you on its cover, chained.

You look exceedingly alone—as alone, say, as the Jewish housewife in the boxcar headed for Dachau, or as any one of our ancestors, chained together in the name of Jesus, headed for a Christian land.

Well. Since we live in an age which silence is not only criminal but suicidal, I have been making as much noise as I can, here in Europe, on radio and television—in fact, have just returned from a land, Germany, which was made notorious by a silent majority not so very long ago. I was asked to speak on the case of Miss Angela Davis, and did so. Very probably an exerciser in futility, but one must let no opportunity slide.

I am something like twenty years older than you, of that generation, therefore, of which George Jackson ventures that "there are no healthy brothers—none at all." I am in no way equipped to dispute this speculation (not, anyway, without descending into what, at the moment, would be irrelevant subtleties) for I know too well what he means. My own state of health is certainly precarious enough. In considering you, and Huey, and George and (especially) Jonathan Jackson, I began to apprehend what you may have had in mind when you spoke of the uses to which we could put the experience of the slave. What has happened, it seems to me, and to put it far too simply, is that a whole new generation of people have assessed and absorbed their history, and, in that tremendous action, have freed themselves of it and will never be victims again. This may seem an odd, indefensibly pertinent and insensitive thing to say to a sister in prison, battling for her life—for all our lives. Yet, I dare to say it, for I think you will perhaps not misunderstand me, and I do not say it, after all, from the position of spectator.

I am trying to suggest that you—for example—do not appear to be your father's daughter in the same way that I am my father's son. At bottom, my father's expectations and mine were the same, the expectations of his generation and mine were the same; and neither the immense difference in our ages nor the move from the South to the North could alter these expectations or make our lives more viable. For, in fact, to use the brutal parlance of that hour, the interior language of despair, he was just a n-----—a n----- laborer preacher, and so was I. I jumped the track but that's of no more importance here, in itself, than the fact that some poor Spaniards become rich bull fighters, or that some poor Black boys become rich—boxers, for example. That's rarely, if ever, afforded the people more than a great emotional catharsis, though I don't mean to be condescending about that, either. But when Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali and refused to put on that uniform (and sacrificed all that money!) a very different impact was made on the people and a very different kind of instruction had begun.

The American triumph—in which the American tragedy has always been implicit—was to make Black people despise themselves. When I was little I despised myself; I did not know any better. And this meant, albeit unconsciously, or against my will, or in great pain, that I also despised my father. And my mother. And my brothers. And my sisters. Black people were killing each other every Saturday night out on Lenox Avenue, when I was growing up; and no one explained to them, or to me, that it was intended that they should; that they were penned where they were, like animals, in order that they should consider themselves no better than animals. Everything supported this sense of reality, nothing denied it: and so one was ready, when it came time to go to work, to be treated as a slave. So one was ready, when human terrors came, to bow before a white God and beg Jesus for salvation—this same white God who was unable to raise a finger to do so little as to help you pay your rent, unable to be awakened in time to help you save your child!

There is always, of course, more to any picture than can speedily be perceived and in all of this—groaning and moaning, watching, calculating, clowning, surviving, and outwitting, some tremendous strength was nevertheless being forged, which is part of our legacy today. But that particular aspect of our journey now begins to be behind us. The secret is out: we are men!

But the blunt, open articulation of this secret has frightened the nation to death. i wish I could say, "to life," but that is much to demand of a disparate collection of displaced people still cowering in their wagon trains and singing "Onward Christian Soldiers." The nation, if America is a nation, is not in the least prepared for this day. It is a day which the Americans never expected to see, however piously they may declare their belief in progress and democracy. Those words, now, on American lips, have become a kind of universal obscenity: for this most unhappy people, strong believers in arithmetic, never expected to be confronted with the algebra of their history.

One way of gauging a nation's health, or of discerning what it really considers to be its interests—or to what extent it can be considered as a nation as distinguished from a coalition of special interests—is to examine those people it elects to represent or protect it. One glance at the American leaders (or figureheads) conveys that America is on the edge of absolute chaos, and also suggests the future to which American interests, if not the bulk of the American people, appear willing to consign the Blacks. (Indeed, one look at our past conveys that.) It is clear that for the bulk of our (nominal) countrymen, we are all expendable. And Messrs. Nixon, Agnew, Mitchell, and Hoover, to say nothing, of course, of the Kings' Row basket case, the winning Ronnie Reagan, will not hesitate for an instant to carry out what they insist is the will of the people.

But what, in America, is the will of the people? And who, for the above-named, are the people? The people, whoever they may be, know as much about the forces which have placed the above-named gentlemen in power as they do about the forces responsible for the slaughter in Vietnam. The will of the people, in America, has always been at the mercy of an ignorance not merely phenomenal, but sacred, and sacredly cultivated: the better to be used by a carnivorous economy which democratically slaughters and victimizes whites and Blacks alike. But most white Americans do not dare admit this (though they suspect it) and this fact contains mortal danger for the Blacks and tragedy for the nation.

Or, to put it another way, as long as white Americans take refuge in their whiteness—for so long as they are unable to walk out of this most monstrous of traps—they will allow millions of people to be slaughtered in their name, and will be manipulated into and surrender themselves to what they will think of—and justify—as a racial war. They will never, so long as their whiteness puts so sinister a distance between themselves and their own experience and the experience of others, feel themselves sufficiently human, sufficiently worthwhile, to become responsible for themselves, their leaders, their country, their children, or their fate. They will perish (as we once put it in our black church) in their sins —that is, in their delusions. And this is happening, needless to say, already, all around us.

Only a handful of the millions of people in this vast place are aware that the fate intended for you, Sister Angela, and for George Jackson, and for the numberless prisoners in our concentration camps—for that is what they are—is a fate which is about to engulf them, too, White lives, for the forces which rule in this country, are no more sacred than Black ones, as many and many a student is discovering, as the white American corpses in Vietnam prove. If the American people are unable to contend with their elected leaders for the redemption of their own honor and the loves of their own children, we the Blacks, the most rejected of the Western children, can expect very little help at their hands; which, after all, is nothing new. What the Americans do not realize is that a war between brothers, in the same cities, on the same soil is not a racial war but a civil war. But the American delusion is not only that their brothers all are white but that the whites are all their brothers.

So be it. We cannot awaken this sleeper, and God knows we have tried. We must do what we can do, and fortify and save each other—we are not drowning in an apathetic self-contempt, we do feel ourselves sufficiently worthwhile to contend even with the inexorable forces in order to change our fate and the fate of our children and the condition of the world! We know that a man is not a thing and is not to be placed at the mercy of things. We know that air and water belong to all mankind and not merely to industrialists. We know that a baby does not come into the world merely to be the instrument of someone else's profit. We know that a democracy does not mean the coercion of all into a deadly—and, finally, wicked— mediocrity but the liberty for all to aspire to the best that is in him, or that has ever been.

We know that we, the Blacks, and not only we, the blacks, have been, and are, the victims of a system whose only fuel is greed, whose only god is profit. We know that the fruits of this system have been ignorance, despair, and death, and we know that the system is doomed because the world can no longer afford it—if, indeed, it ever could have. And we know that, for the perpetuation of this system, we have all been mercilessly brutalized, and have been told nothing but lies, lies about ourselves and our kinsmen and our past, and about love, life, and death, so that both soul and body have been bound in hell.

The enormous revolution in black consciousness which has occurred in your generation, my dear sister, means the beginning or the end of America. Some of us, white and Black, know how great a price has already been paid to bring into existence a new consciousness, a new people, an unprecendented nation. If we know, and do nothing, we are worse than the murderers hired in our name.

If we know, then we must fight for your life as though it were our own—which it is—and render impassable with our bodies the corridor to the gas chamber. For, if they take you in the morning, they will be coming for us that night.

Therefore: peace.

Brother James

November 19, 1970

Sunday, September 25, 2011

Saturday, September 24, 2011

Friday, September 23, 2011

Thursday, September 22, 2011

Thoughts Running Through My Head...

"It is our duty to undermine systems of oppression"-to quote myself.....does this make me an anarchist?..I have never considered myself such...it is as natural for me as Corrie Ten Boom hiding Jews in the walls of her house....and her legacy has been a deep influence on me...Papa Ten Boom didn't think twice...because he knew what was right...and died on a hospital gurney outside of his bed...

RIP Troy Anthony Davis....May your spirit live and be infectious....

Monday, September 19, 2011

Interview with Daniel Joseph Baker

Daniel Joseph Baker is clearly the most talented person to have graced the stage of this season's America's Got Talent. It came as a jilting shock to all of us who embraced this magnificent spectacle of talent and actually decided to tune in every week just to see him when he was eliminated. No matter. Daniel is a raw talent, possessing an animal magnetism that puts him in the tradition of Labelle, Grace Slick, and Lady Gaga. I recently got in touch with him via Facebook and asked him if I could interview him for my blog. Graciously, he agreed. This is what transpired.

1. How long have you been a singer and performer?

Since I was 6 years old at Church baptisms.

2. What made you try out for AGT?

I was very unhappy with the status of my life. I feel like it was worth continuing. I had a dream of performing on television, so that unhappiness drove me to audition for AGT on a whim.

3. What is your greatest aspiration?

To have a career in the entertainment industry.

4. Who are the major influences on your music?

Nicole Scherzinger, Lady Gaga, & Christina Aguilera. These are the only 3 people I look towards for ideas & inspirations for my next performances!

5. What is your background and where are you from?

I was raised in a mormon household & was born in Washington state.

6. Did you like the environment you grew up in? Did it nurture your creativity?

I loved my childhood. My parents never got mad at me for singing & banging on the piano during all hours of the night. They wanted me to continue perfecting my talents.

7. Have you been embraced by any gay celebrities? Which ones?

Raja from drag race tweeted me. That was my favorite!

8. How has fame been treating you?

I don't consider myself famous at all.

9. How would you describe your personal style? Where did the leg-on-the-piano thing come from?

My personal style: FIERCE. Foot on the piano: (any monster knows this) GAGA

10. How was your experience on AGT?

Best experience of my life so far. No negatives to list at all. It gave me so much confidence.

11. Where did you normally perform before AGT?

I performed in church and school growing up. But in recent years, only in my house.

12. Were you shocked when you were eliminated?

I was shocked at first. But I've always kept in mind that anything is possible. I want to thank my fans for supporting me through it.. Everything happens for a reason.

13. Of any artists past or present, who would you want to emulate in terms of your career?

I love Liberace & Elton John. I also love Cher & Nicole Scherzinger. I WANNA BE A PUSSYCAT DOLL!

14. Do you have anything in the works?

.I've been booking gigs & am moving to Hollywood! Danfans should look out for me!!

Thanks, Daniel!

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

Friday, August 26, 2011

Thanks, Corey, I am STEALING!!!

Wednesday, August 17, 2011